Billy Taylor’s Proven He’s One-Of-A-Kind; Now He’s A Dirt Mod Hall Of Fame Mechanic

Story By: BUFFY SWANSON / NORTHEAST DIRT MODIFIED HALL OF FAME – WEEDSPORT, NY – Crafting a career as a first-class car chief, owner and innovator during the past six decades, Billy Taylor will be honored with the distinguished Mechanic/Engineering Award during the 2020 Hall of Fame ceremonies, scheduled for Thursday, July 23, at the Northeast Dirt Modified Museum and Hall of Fame on the grounds of Weedsport Speedway in New York.

From Ellenburg Depot, NY, Taylor started out helping ’60s racers like Bill Wimble and Dick Goodell at Plattsburgh and tracks north of the border as a teenager. After his family moved to Rochester in the early 1970s, Taylor hooked up with Richie Evans at Spencer Speedway and traveled the circuit with the NASCAR Modified superstar for the next three years.

After Evans, Taylor continued to work for other top blacktop titans: a lengthy stint turning wrenches for Maynard Troyer was followed by a position on Dick Armstrong’s race team, as crew chief for driver Geoff Bodine. That necessitated Billy’s move to Massachusetts where he worked alongside car builder Ralph “Hop” Harrington on one of the most successful teams in paved-track Modified history: in 1978, the Armstrong entry — built by Harrington, driven by Bodine, crewed by Taylor — won 55 races in 84 starts, including the Race of Champions at Pocono, Stafford Spring Sizzler, Budweiser 200 at Oswego, both major events at Martinsville, the Thompson 300, and a sweep of the Yankee All-Star League Series.

After Bodine moved up and south to the NASCAR Cup Series, Taylor returned to his roots in New York, opening his own race car shop in Sodus in the mid ’80s. By that time, his old ally Maynard Troyer was manufacturing Mud Busses — and Taylor turned his attention to dirt.

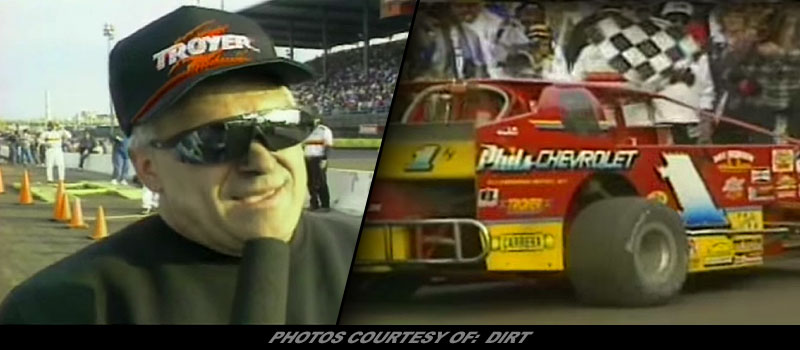

With sponsorship from his brother Phil’s Chevrolet dealership and Phelps Cement, Taylor debuted a gorgeous Troyer dirt Mod with a Hutter under the hood in the spring of 1987. The car was specifically constructed for Sprint star Sammy Swindell to drive in select DIRT specials. But Swindell drove it only once, to a tenth-place finish at Rolling Wheels, before Taylor tapped Alan Johnson for the spot. Driving for Taylor on a limited basis, A.J. ran the car five times total in June, scoring three wins (a regular show at Canandaigua, a 100-lapper at Utica-Rome and Ransomville’s Summer Nationals) before exiting to reunite with his former car owner Tico Conley.

Next up: Alan’s brother Danny. Three days after Alan’s tour de force in the Summer Nationals, Taylor offered the ride to Danny Johnson for a 100-lap holiday event at Rolling Wheels.

“I figured if I didn’t drive the car, I’d get beat by it,” Danny said, and reeled off the Taylor team’s fourth win in seven starts.

On board for Taylor’s “specials only” schedule, D.J. rattled off another 10 victories that season, including four 50-lappers at Canandaigua and Weedsport, and a pair of Super DIRT Series races in Canada and New York.

“He’s got a helluva team, a helluva motor,” Danny said of Taylor’s operation in one victory lane speech that summer. “What can I say? It’s a winning car.”

DIRT’s asphalt series, which ran from 1988-92, seemed custom-made for Taylor with his vast paved track experience.

“It fell right in my pocket,” Billy chuckled about DIRT’s decision to take up tar racing. “I knew exactly what I wanted to do and how to do it. I was [chief tech inspector] Bob Dini’s worst headache.”

Taylor was clever enough not to carry anything over from the clay: his DIRT-Asphalt cars were purpose-built, by Bodine-connected Chassis Dynamics and Troyer, both geniuses of the genre. From his pavement days, Billy understood the advantage of running a “big” Buick 430 CID small-block over the standard big-block engine that was large on brute power but light on finesse.

It was a different way of doing things, as Taylor explained to driver Danny Johnson at Canada’s Cayuga Speedway in August of ’89.

In the asphalt car, “I got spun out by Kenny Schrader, in either hot laps or the heat race,” Danny recalled. “When I came back in the pits, Billy told me how I had to drive it. ‘Gingerly,’ he said. ‘Get on it as tenderly as if there was an egg under the gas pedal.’”

Actually, Johnson wasn’t even slated to drive for Taylor that day at Cayuga: D.J. was a last-minute replacement for Billy’s buddy Geoff Bodine, who’d carried the car to a previous series win at Thompson. When Bodine took ill, Taylor tagged Danny — who started eighth in the unfamiliar ride and blitzed both Bob McCreadie and Jimmy Horton for the win.

With his meticulously prepared equipment that always pushed the tech envelope, Taylor had his pick of the top talent. Alan, Danny and Jack Johnson, Kenny Brightbill and Geoff Bodine all won for Taylor; Dave Blaney (runnerup twice at Super DIRT Week for Taylor), Sammy Swindell, Mike McLaughlin, Gary Balough, Bob and Tim McCreadie, Jimmy Horton, Charlie Rudolph, Steve Paine and Ricky Elliott all drove for him.

But his greatest success came with Pennsy ace Doug Hoffman.

Off and on, from 1990-96, Taylor and Hoffman synched to score 19 times at 13 tracks, on dirt and asphalt, in four states and Canada. Included in that win total were seven SDS events, a pair of Lebanon Valley 200s, two Fonda 200s, 200-lappers at Bridgeport and Flemington, a couple of holiday events at the NYS Fairgrounds — and the crown jewel of them all, the October classic at the Syracuse mile in 1996.

They claimed four big wins, the 1991 championship, and $157,575 in prize and point money in the DIRT-Asphalt Challenge Series.

But the Syracuse brass ring, maddeningly elusive for both owner and driver to catch throughout their careers, was the high point.

“Four years before that, we were driving away in that race. We pitted, we thought we were in a good position — and then the rain came,” Taylor lamented.

It certainly didn’t rain on their parade in ’96. “We had built a brand new Mud Buss, unloaded it — and it was a Cadillac,” Billy recounted. “I liked it, Doug liked it. He could sit up straight and pay attention. We made the right decisions, and checked out.”

Not long after that career highlight, Billy’s brother Phil — his biggest supporter, in racing and in life — succumbed to a brain tumor.

“That’s when I started looking to move down south,” said Taylor.

These days, Taylor works for JR Motorsports in Mooresville, NC, building electric systems for the team’s NASCAR Xfinity cars.

“He does it because he wants to, not because he has to,” son Adam said of his 74-year-old dad’s full-time job. “He still loves it.”